Contrast this to art. With art, if you paint the Sistine chapel, well, you painted the Sistine Chapel. If you wrote War and Peace, you wrote War and Peace. There's no such thing as coming in second, because works of art are unique (or at least, have been unique up until the contemporary period, thanks to folks like Andy Warhol). Then again, all works of art flow historically from all previous works of art. Individual achievement incorporates prior achievements by others. Nowadays it's as simple as sampling a riff from a Beatle song, but for the Beatles, it was the absorption of the music that preceded them, the blues and skiffle and swing, and transforming it into Beatle music. Of course, samplers will insist that they are part of this tradition, and they may be right!

Creativity is a wondrous subject.

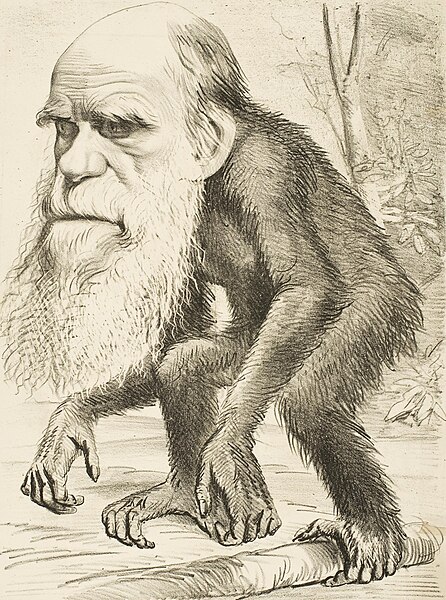

Ian McEwan compares scientific creativity with artistic creativity in an article for The Guardian. He begins by telling the story of Darwin and Wallace. They had both been working on the subject of evolution, but Darwin hadn't published (although he had begun his work prior to Wallace), and then he received Wallace's papers, to make them public. Darwin was put in the position of having been the first, but making himself look like the second. Fired up by a sense of purpose, he wrote The Origin of Species. And that sense of purpose was informed by one thing:

Ian McEwan compares scientific creativity with artistic creativity in an article for The Guardian. He begins by telling the story of Darwin and Wallace. They had both been working on the subject of evolution, but Darwin hadn't published (although he had begun his work prior to Wallace), and then he received Wallace's papers, to make them public. Darwin was put in the position of having been the first, but making himself look like the second. Fired up by a sense of purpose, he wrote The Origin of Species. And that sense of purpose was informed by one thing:The Origin, written in 13 months, represents an extraordinary intellectual feat: mature insight, deep knowledge and observational powers, the marshalling of facts, the elucidation of near-irrefutable arguments in the service of a profound insight into natural processes. The reluctance to upset his wife Emma's religious devotion, or to contradict the theological certainties of his scientific colleagues, or to find himself in the unlikely role of iconoclast, a radical dissenter in Victorian society, all were swept aside for fear of another man taking possession of and getting credit for the ideas he believed to be his.

In a word, Darwin couldn't abide not being the first.

McEwan's article covers a lot of philosophic, scientific, artistic and humanistic ground. It's called The originality of the species. It's worth a look.

No comments:

Post a Comment